4. Theoretical Innovations in Aesthetics (Part II)

The study of aesthetics is embedded in the branches of knowledge of philosophy, art, architecture, and the behavioral sciences. In essence, appreciating beauty in architecture is a factor of the inner human feelings experiencing the architecture and of the qualities of the architecture itself. Both subjective and objective factors are believed to influence one's aesthetic appreciation of architecture, which in turn varies over time and across people suggesting that individual characteristics and trends of the time affect the judgments of beauty. Consequently one needs to know and understand the prevailing aesthetic beliefs of the time.

2. Environment & behavior theories of aesthetics

Environmental and behavior theories of aesthetics are the contribution of the behavioral sciences to the environmental design fields of architecture and urban design. Understanding visual perception is the essence of understanding or explaining aesthetics in the behavioral sciences. This is the main premise of environmental perception and its role in aesthetic development. Aesthetics under the environment behavior approach is termed environmental aesthetics . Environmental and behavior theories of aesthetics rely on scientific methods, empirical research, and on the relationship between people and environments. Some of these theories have direct application in architecture, while others remain to be fully appreciated by architects. Much research and effort is needed from both practitioners and researchers to bridge the gap between theories of aesthetics in general and architectural applications. The following is a review of several key advances in aesthetic theory.

-

Gestalt theory of aesthetics

Gestalt theory of aesthetics is embedded in the Gestalt Psychology, founded by Max Wertheimer in Germany early 20 th C., that primarily deals with the perception of forms and shapes. This epistemological movement in psychology rejected the analytical method in the study of human behavior; it called for experimental methods instead, for studying complex visual phenomena. It regards visual perception as global, holistic, integrated with human behavior, favoring a dynamic interpretation of behavior; people respond to environments as entities in an integrated way. In essence, Gestalt Psychology was a reaction to reductionism claiming that studying perception using separate basic elements was insufficient. It emphasized dynamic and organizational nature of perception. According to Gestalt ideology, human interaction with architectural expression is direct, biological, & independent on prior experience. From the study of visual perception in the manner described, including the study of optical or visual illusion, a number of principles called the Principles of Organization were deduced that are essential for a successful and favorable visual perception of scenes. Grouping (including proximity, similarity, continuity, and closure) and figure-ground relationship are the two principles of organizations. These principles had a huge impact on art and architecture for generations. Elements derived from Gestalt studies such as unity, harmony, contrast, rhythm, repetition, gradation, balance, dominance / emphasis become known as design principles in architecture and in art compositions. Geometric elements such the point, line, plane, and the volume became known as the elements of design in both architecture and in art. The Bauhaus School of Architecture in Germany (1919-1933) headed by Walter Gropius was based upon the principles of Gestalt Psychology. The school's influence on the International style, which was later criticized, extended for decades. In short, this theory claims that organization & patterns are an integral part of perception that is important in favorable aesthetic reactions. Some of the criticisms regarding this theory such as the less emphasis on past learning and on higher order intellectual processes, more emphasis on formal aesthetics, geometric qualities, 2d shapes, have left the theory dealing with supposedly unrealistic and perhaps incomplete understanding of human-environment interactions; other theories emerged as a result.

-

Experimental aesthetics

Daniel Berlyne (cf. 1974) was among the pioneers of modern experimental aesthetics. He proposed a theoretical model of aesthetics, which stresses upon the importance of four key visual attributes, sometimes called the collative stimulus properties : complexity; novelty; incongruity; surprisingness.

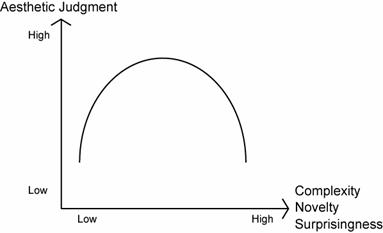

Berlyne further distinguished between two types of exploration. Diversive exploration occurs when one is seeking arousing stimuli to fulfill an existing state of lack of stimulation. Specific exploration, on the other hand, occurs when stimulation already occurs and one is trying to understand or make sense of this stimulus to reduce uncertainty and fulfill one's curiosity. From these definitions, Berlyne theorizes that aesthetic judgment occurs along two dimensions: the conflict-arousal and the hedonic tone. Arousal associated with specific exploration increases when uncertainty or conflict increases. But when uncertainty increases, hedonic tone (degree of pleasantness) increases up to a point then decreases, suggesting an inverted-U shape curvilinear relationship. In other words, people feel happiest when exposed to intermediate levels of visual stimuli or uncertainty, and not with excessive stimulation or arousal. This theory therefore suggests that architecture providing intermediate levels of complexity, novelty, and surprisingness will generate the most positive judgments of aesthetic appreciation. Conversely, high or low levels of complexity, novelty, and surprisingness in environments would be judged as less beautiful or even ugly (Figure 1).

Figure (1): The relationship between collative properties & aesthetic judgment

In short, this theory determines aesthetic judgment upon how one resolves the perceptual conflict exposed to in the built environment in terms of the aforementioned properties, hence the name collative stimuli properties . Berlyne's work has been criticized in its reliance on objective kind of visual stimuli and disregarding individual's subjective influences.

-

Model of Environmental Preference

Steven and Rachel Kaplan developed the so-called model of environmental preference that takes into account the psychological influences of individuals in affecting the outcome of aesthetic judgments (Kaplan & Kaplan, 1983; 1989). Focusing upon information processing and cognitive phases of perception, they came up with a two-by-two matrix explaining preferences for environments (Table 1).

Making Sense

Involvement

Present or Immediate

Future or Promised

Table (1): The Kaplans Model of Environmental Preference

People seek information in the environment. Consequently, they require information processing to make sense of their surrounding (the need to understand) and to get involved with the surrounding (need to explore). Coherence & legibility are preferred attributes for the purpose of understanding, while complexity & mystery are preferred attributes for the purpose of exploration. This model involves two important dimensions: content and spatial organization. The presence of nature is an example of content. Spatial organization involves degree of openness and spatial definition. These dimensions are important and consistent with the formal-symbolic dichotomy characterizing aesthetics. In short, this theory assumes that people will like scenes that stimulate their urge for information processing and are successful in processing. People would prefer scenes that are understandable and make sense (having the attributes of legibility and coherence), those that are engaging and involving (having the attribute of mystery, without fear), and those that are not too simple or too dull (such as having intermediate level of complexity).

-

Landscape research

Landscape research has provided evidence and guidelines that enhance our understanding of the theory of landscape aesthetics. Landscape research attempts to determine what makes a landscape beautiful, how to preserve its beauty when human-made elements are introduced such as roads, why and how do people differ and agree as to beautiful landscapes. In the US , research in this area has boomed coinciding with the introduction of governmental legislation in the 1960s and 1970s that preserves scenic landscapes. Zube, Sell and Taylor 's (1982) classic review of landscape research has provided a theoretical classification of types of research in this field that is still in tact today (see also Taylor, Zube & Sell, 1987; Bell et.al., 1997). The first approach is the descriptive approach where experts describe landscape based on their experience and artistic judgment. Detecting contrast or observing focal points in nature scenes are examples of what can contribute to positive evaluations of scenic quality. This approach is consistent with the landscape architects' approach and interest in design. It has been, however, criticized of being weak in validity and reliability issues. The second approach, which is more grounded in empirical research, is the physical-perceptual approach or psychophysical approach. This approach assumes that physical elements in the environment act as stimuli to which users or viewers receive and respond. It basically attempts to quantify the physical features of the environment. Examples of factors of scenic quality derived through this approach include area of immediate vegetation, area of water, adjacent land use, relative relief (topography), ruggedness, naturalness (Shafer, Hamilton & Schmidt, 1969). Other examples include slope of the ground, tree canopy, and vegetation coverage as positive predictors of aesthetic preferences (Im, 1984). This approach has been criticized by being weak in theoretical formulations and for its generalizability among different settings but praised for its focus on the objective features of the environment and for its introduction of psychological processes of perception. The third approach, the psychological or cognitive paradigm, focuses on the psychological or cognitive principles and processes that affect aesthetic judgments. Examples include attributes such as complexity, coherence, mystery and legibility as possible predictors of aesthetic preferences. This approach is praised for being more theoretically grounded with different theoretical models available in the literature (Kaplan et.al., 1989) and for over reliance on psychological concepts and processes. The fourth approach, labeled the experiential or phenomenological, relies on describing the holistic and subjective experiences of human beings in their environments and consequent feelings of aesthetics. This approach is often at odds with the empirical methodology used of the previous two approaches. Table (2) summarizes these four approaches.

Study Approach

Description

1. Expert approach

Experts describe landscape based on their experience and artistic judgment

2. Physical-perceptual / psychophysical approach

Assumes that physical elements in the environment act as stimuli to which users or viewers receive and respond and attempts to quantify the physical features of the environment

3. Psychological or cognitive approach

Focuses on the psychological or cognitive principles and processes that affect aesthetic judgments

4. Experiential or phenomenological approach

Describes the holistic and subjective experiences of human beings in their environments and consequent feelings of aesthetics

Table (2): Classifications of research in landscape aesthetics

-

Restorative effect of nature

It is the premise that visiting natural settings or viewing natural scenes may have a restorative effect on human beings. Either of two theories claims to explain the reasons why nature has a restorative effect: stress reduction or attention restoration theory. Stress reduction theory postulates that “humans should have a biologically prepared affiliation for certain restorative natural settings” ( Bell et.al., 2001, p.48). This functional-evolutionary paradigm, which resembles the biophilia in landscape research, shows that exposure to specific types of natural scenes, may lead to restorative responses such as reduced physiological stress, reduced aggression, and a restoration of energy and health. Interestingly, this explanation does not apply to the urban environment (Urlich, 1991). The attention restoration theory (ART) provides another explanation for the restorative effects of nature (Kaplan et.al. 1989; Kaplan, 1995). Directed attention is required to perform stressful tasks. By time and increased effort, directed attention may get weaker reaching a state of fatigue. The attention restoration theory hypothesizes that effortless attention acquired by the fascination with viewing certain natural scenes will lead to restored attention. The key to restoring or recharging one's directed attention in this theory is the exposure to an attention that is different, instinctive, and requires little or no effort, which can be achieved by getting fascinated with watching nature scenes. Research have suggested elements of nature that would create this fascination or “soft fascination” that requires little effort to capture one's attention such as clouds, sunsets, or leaves flickering in the sunlight. However, certain elements of nature such as snakes and spiders may create fascination but because they are incompatible with human needs and wants this type of effortless attention would not lead to restorative effects. Applications of these theories on the use of nature in urban settings are lacking.

- Prospect and refuge theory

Jay Appleton's (1975; 1984) prospect and refuge theory is related to information seeking and understandable information and has its roots in human biology. Prospect refers to having open, unobstructed views. Refuge refers having safe and sheltered places to hide. Prospect presents speedy understanding of the visual information in the environment, thereby resulting in a more preferred visual experience. Refuge offers a kind of curiosity also contributing to a more positive response to the visual scene by increasing visual attractiveness. Refuge was manifested in architecture in the desire of “seeing without being seen.” Applying his study on natural environments, Appleton compares humans with animals' inherent quest for survival and shelter seeking.

A more general habitat theory suggests that humans prefer environments that satisfy their biological needs namely that of survival. This suggests that preference is related to a “live-in” rather than a “look-at” experience (Porteous, 1996). The more specific prospect refuge theory is based upon the hunting experience. Porteous (1996) describes this analogy quite well by saying:

“The hunter needs to be able to view the pray (prospect) while hiding (refuge) until the final dash is made. The huntee must have wide vistas all around (prospect) plus the chance of getting away to a hidden place (refuge).” (Porteous, 1996, p.25-26).

Consequently, creatures explore the environment to seek open opportunities of vision (prospect) and opportunities for hiding (refuge). In that respect, environments having both attributes, prospect and refuge, are aesthetically pleasing. To further emphasize the innate nature of this reaction, images of nature depicting the African Savannah were found to be highly preferred compared to other types of natural scenes. This conclusion led biological supporters of biological interpretations of aesthetic judgments to explain this result by bringing up the hypothesis that Homo sapiens are believed to have originated in the African savannah environment, thus instinctively attracted to it. This theory, however, remains largely untested for the urban environment.

-

Theory of affordances

James Gibson's theory of affordances (1986) stems from his ecological approach to perceiving the environment. He argues that meaning is inherently embedded into the environment and all humans have to do is decipher them. Ecological perception of the environment is thereby dynamic and mobile, more direct with less emphasis on cognition (or higher levels of processing the information), and more holistic in that environmental features are perceived in a meaningful entity as a whole; the latter of which is similar to Gestalt perception in this regard. Characteristics of the environment are perceived as either affording a certain activity or meaning or not. These perceived characteristics he called the object's invariant functional properties such as surface, texture, and angle of view. These properties become affordances (a noun that he invented) if perceived as meaningful and affording a certain activity. For example a hard surface parallel to the floor may afford sitting. Therefore beautiful scenery for example can be achieved by altering the environment in a way that affords that aesthetic objective. The following is a quotation from his writing:

“I have described the environment as the surfaces that separate substances from the medium in which animals live. But I have also described what the environment affords animals, mentioning the terrain, shelters, water, fire, objects, tools, other animals, and human displays. How do we go from surfaces to affordances? And if there is information in light for the perception of surfaces, is there information for the perception of what they afford? Perhaps the composition and layout of surfaces constitute what they afford. If so, to perceive them is to perceive what they afford. This is a radical hypothesis, for it implies that the “values” and “meanings” of things in the environment can be directly perceived. Moreover, it would explain the sense in which values and meanings are external to the perceiver.” (Gibson, 1986, p.127)

Even though Gibson was not an architect, his theory had an impact on architectural design (Cooper, 1992). More specifically, Gibson identified visual texture or textural gradient as a sufficient condition for visual perception. Visual texture included surface characteristics, different scales, and all sorts of shapes. He consequently identified depth cues as secondary condition for the perception of the visual field. This has helped him develop our understanding how overlapping and perspective produce perceptions of depth.

-

Environmental Aesthetics

Environmental aesthetics is the term used to cover all the theories of environment behavior aesthetics that are generally empirically based. The theories presented fall under one of two modes of or approaches to the study of perception. The constructivism model treats perception as an active process where sensory stimuli or information are analyzed, compared with past experience, manipulated and perceptual judgments made; i.e. cognition takes place. Examples of this approach are the Kaplans' model and others in landscape research. The nativistic approach treats perception as a direct process where it is biologically caused and environmentally embedded; i.e. cognition is unnecessary. Examples of this model are the biophilia and Gibson's affordances.

Aesthetics are generally classified into two kinds: formal and symbolic aesthetics (Lang, 1989). Formal aesthetics include dimensions such as shape, proportion, scale, complexity, novelty, illumination, coherence, order, enclosure, mystery, openness, spaciousness, density, etc. Symbolic aesthetics include various forms of meaning, whether denotative such as function and style, or connotative such as friendliness and imposition. Naturalness, upkeep, and intensity of use are other sources of symbolic aesthetics (Nasar, 1994).

Attributes are the cognitive attributes (qualities, characteristics) that viewers perceive & cognize from seeing the physical features. Attributes, according to Lang (1987), Nasar (1994a) and others, are classified into formal and symbolic. Formal aesthetics “deals with the appreciation of shapes and structures of the environment for their own sake” (Lang, 1987, p.180); it is also defined as “human aesthetic experience in relation to the formal or structural parts of the work” (Nasar, 1994a, p.12). Symbolic aesthetics are “concerned with the associational meanings of the patterns of the environment that give people pleasure” (Lang, 1987, p. 180); it is also defined as “pleasurable connotative meanings associated with the content of the formal organization” (Nasar, 1994a, p.13). These dimensions have been further differentiated between physical features of the environment or cognitive attributes of the environment (Gabr, 2004).

A clear distinction made in environmental aesthetics is the separation between features and attributes of the environment. Features of the environment are the physical features or elements (architectural, urban, and natural) that viewers see (notice) and perceive. Examples include windows, doors, roof, height, bricks, trees, green areas, plants, and water. For purpose of better benefiting from features in design, they have been categorized into fixed feature elements such as those mentioned above, semi-fixed feature elements such as furniture, and non fixed feature elements such as people and their behavior in space (Rapoport, 1990). Architects typically have more control over the fixed features, less on the semi-fixed and the least on the non fixed. Yet the reverse order seems to be more influential in generating meanings to the public. Accordingly non fixed features produce more meaning than the semi-fixed or fixed features.

Tables (3) and (4) summarize a number of key attributes resulting from environment and behavior research that affect aesthetic design and judgment. Clearly the emphasis is on the formal attributes. Future research has do undertake the challenge of examining symbolic attributes as they are fundamentally important in determining aesthetic quality. Beautification of cities can take the form of cosmetic treatments without regard to function or meaning or it can take a more meaningful treatment that accounts for the function and use of the buildings and spaces. Cosmetic aesthetics are often undesirable as they do not gain public support and appreciation. Instead, meaningful aesthetics are desirable with which the public tend to interact more positively. This also coincides with the notion of aesthetics as not just representing a visual experience but that involves the experiences of all other senses, hearing, touching, smelling, and tasting.

Table (3): Formal attributes of environmental aesthetics

Formal Attribute

Definition

Complexity

(Diversity, visual richness)The extent to which a variety of components make up an environment ( Bell et.al. 2001, p.41-42)

Novelty

(particularity, atypicality)The extent to which an environment contains new or previously unnoticed characteristics ( Bell et.al. 2001, p.41-42)

Incongruity

The extent to which there is a mismatch between our environmental factor and its context ( Bell et.al. 2001, p.41-42)

Surprisingness

(unexpectedness)The extent to which our expectations about an environment are disconfirmed ( Bell et.al. 2001, p.41-42)

Coherence

(order, organization)The extent to which the scene “hangs together;” the extent to which architectural features are consistently arranged to form a recognizable pattern, order or uniformity

Legibility

(orientation, navigation)The ease with which people can understand the opportunities offered by the place on where to go for desired destinations & how to get there

Mystery

(suspense, uncertainty)The extent to which environmental features are arranged in such a way as to offer promise for additional information

Prospect

(vistas, panorama)The extent to which scenes are composed in a way that can be effectively discovered & related visually

Refuge

The extent to which a scene imparts a sense of security or protection

Contextual compatibility

The extent to which architectural features match with the surrounding features in terms of visual organization, style, etc. (Figures 39, 40)

Authenticity

(real, genuine)The extent to which the environment &/or human activities in the scene are perceived as genuine

Spaciousness

(space, depth)The extent to which the environment conveys a sense of abundant space & depth of visual field & room to wonder

Naturalness

The extent to which environmental features are predominantly natural

Visual organization

The extent to which environmental features are arranged so as to create visual harmony as a whole & in relation to one another

Visual affordances

The extent to which users employ environmental cues to fulfill their functional goals (plans of action) (J. Gibson)

Visual exploration

The extent to which the environment offers directions for visual exploration (J. Gibson)

Visual navigation

The extent to which the environment offers the opportunity for easy & clear knowledge of where to go to desired destinations & how to get there (J. Gibson)

Table (4): Symbolic attributes of environmental aesthetics

Symbolic Attribute

Definition

Style

Represents a mentally constructed “characteristic formal organization” in relation to the system of forms

Cleanliness

The extent to which the environment is clean & unpolluted

Upkeep/civility

The extent to which the environment is well maintained & cared for

Historical significance

The extent to which the viewer perceives elements in the context as historically important

Copyright © 2005, Hisham Gabr