2. The Study of Aesthetics

Fields of knowledge interested in the study of aesthetics have been mostly philosophy, art, architecture, and the behavioral sciences. Each field has dealt with aesthetics from their own perspective, serving their own purposes, and reflecting their own world views and ideologies. Each field has therefore defined aesthetics in distinct ways reflecting their approach to aesthetics. Nevertheless, many similarities do occur among these different approaches, pointing toward several common issues. This section introduces the study of aesthetics by defining the term and discussing the reasons why the study of aesthetics is important. The discussion brings up the differences as well as the similarities among the various fields of knowledge. However, the emphasis is placed upon the contributions of the behavioral sciences in particular on architectural and urban aesthetics, thereby pointing towards innovations in the study of aesthetics. The interest in studying aesthetics raises a number of important questions. Who, what, why, and how to study aesthetics becomes the focus of attention.

-

Who studies aesthetics?

Determining who is interested in studying aesthetics affects the study approach towards the concept. Moreover, it sheds light on determining who is supposed to judge what is beautiful and based on which values and criteria; a topic of significance yet difficult to handle and is often controversial.

Historically, the study of aesthetics has been considered a branch of philosophy. Aesthetic philosophy has been a significant part of the philosophical work of Plato and Aristotle in old times, of Kant and Santayana among others in more recent times.

Related to philosophy is the artistic interest in aesthetics. Art is supposed to be beautiful almost by definition because art is a quest for pure aesthetic enjoyment in addition to it attempting to fulfill social aspirations (Barons, 1997). The social motivation of art broadens the view of aesthetic enjoyment.

Architecture's profound interest in aesthetics is as old as the profession. The three common goals of architecture that stood the test of time are commodity (utility/function), firmness (structure/stability), and delight (i.e. aesthetics). Vitruvius's treatise, The Ten Books of Architecture (1960), exemplifies principles of design in old times. Among his treatise, he specifies the term eurythmy, which he defines as “beauty and fitness in the adjustments of the members (of a work)” (p.14), as one of the fundamental principles of architecture. Rasmussen's Experiencing Architecture (1962) exemplifies a more recent attempt in underscoring principles of aesthetic design.

The involvement of the behavioral sciences in aesthetics since the second half of the twentieth century brought innovative contributions to aesthetics, both theoretically and applied. The origin of behavioral science involvement in the study of aesthetics probably goes back towards the latter part of the nineteenth century (Abdel-Hamid, 2004). Involvement picked up systematically around the second half of the twentieth century. Behavioral sciences have been contributing and can continue to play a part in the field of architecture and urban design aesthetics. Table (1) compares disciplines that study aesthetics illustrating common interests, biased interests, and critical issues.

Field of Knowledge

Philosophy

Art

Architecture

Social Sciences

Common Issues

Common issues or questions that each field attempts to resolve:

Beauty is in the person or the object?

Which are more reliable, subjective approaches/factors or objective approaches/factors?

Who has the right to judge what is beautiful, the expert or non expert, designer or user?

Does aesthetic response vary over time and across people?Emphasis

Rational; based on reason; logical; qualitative measures

Artistic; emotional; subjective; qualitative measures

Eclectic; stylistic; pluralistic; personal; practical; expert-defined; qualitative (or quantitative); idiosyncratic

Empirical; scientific; user-defined; quantitative (or qualitative)

Criticism

Too abstract

Non-scientific

Quasi-scientific

Link to practice

Sample of Scholars

Plato, Kant, Santayana

Arnheim, Kofka, Picasso, Turner

Le Corbusier, Venturi, Alexander, Krier, Rasmussen

Berlyne, Kaplans, Nasar, Herzog, Wohlwill, Urlich

Table (1): Comparison of disciplines interested in the study of aesthetics

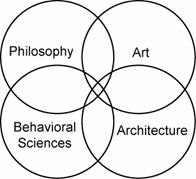

It should be noted that these discipline overlap in several ways. Philosophy and art coincide at times, art and architecture coincide many times, and the behavioral sciences also coincide with architecture, and so on. Figure (1) illustrates the overlapping of different disciplines in the interest of aesthetics.

Figure (1): Fields of knowledge overlapping interest in the study of aesthetics

-

What is aesthetics?

Defining aesthetics has been influenced by the branch of knowledge it reflects. Many definitions exist and a consensus on one single, universal definition is unavailable. The following are some definitions from various sources that show some similarities among them.

Aesthetics is defined in the Philosophical Dictionary as follows:

“Branch of philosophy that studies beauty and taste, including their specific manifestations in the tragic, the comic, and the sublime. Its central issues include questions about the origin and status of aesthetic judgments: are they objective statements about genuine features of the world or purely subjective expressions of personal attitudes; should they include any reference to the intentions of artists or the reactions of patrons; and how are they related to judgments of moral value? More specifically, aesthetics considers each of these issues as they arise for various arts, including architecture, painting, sculpture, music, dance, theatre, and literature.” (Philosophy Pages, 2005, p.1)

In the Encyclopedia Britannica, aesthetics is defined as follows:

“Theoretical study of beauty and taste constituting a branch of philosophy. The term aesthetics, derived from the Greek word for perception (aisthesis), was introduced by the 18th-century German philosopher Alexander Baumgarten to denote what he conceived as the realm of poetry, a realm of concrete knowledge in which content is communicated in sensory form. The term was subsequently applied to the philosophical study of all the arts and manifestations of natural beauty.” (Britannica, 2002)

The Merriam Webster Collegiate Dictionary (2002) defines aesthetic or aesthetical, as an adjective, as follows:

“(1798)

1a: of relating to, or dealing with aesthetics or the beautiful <aesthetics theory>;

b: artistic <a work of aesthetic value>;

c: pleasing in appearance, attractive <easy to use keyboards, clear graphics, and other

ergonomic and aesthetic features>;

2: appreciative of, responsive to, or zealous about the beautiful; also: responsive to or

appreciative of what is pleasurable to the senses.”The same dictionary (2002) defines aesthetic, as a noun, as follows:

“(1822)

1: pl. but sing. or pl. in const. : a branch of philosophy dealing with the nature of beauty, art,

taste and with the creation and appreciation of beauty;

2: a particular theory or conception of beauty or art: a particular taste for or approach to what is

pleasing to the senses and especially sight <modernist aesthetics><staging new ballets which

reflected the aesthetics of the new nation>;

3: pl. a pleasing appearance or effect: beauty <appreciated the aesthetics of the gemstone>”One of architecture's main aims is to design settings that evoke pleasing responses from people viewing these settings. The study of aesthetics in architecture, with an environment behavior contribution, attempts “to identify, understand, and, eventually, create those features of an environment that lead to pleasurable responses” (Bell, Greene, Fisher, & Baum, 1998, p.389).

Beauty is a synonym of aesthetic. The Dictionary of the History of Ideas traces the history of the word beauty as follows:

“In English the term beauty goes back to the French beauté, which in turn is derived from a conjectured vulgar Latin bellitatem, formed after the adjective bellus, which neither originally nor properly designated something beautiful; pulcher and formosus had this function. Bellus was a diminutive of bonus (good) and was used first for women and children, then ironically for men. Its affectionate overtones are said to explain why bellus (and not pulcher) was adopted in the Romance languages, where it survived either alone or jointly with formosus. The German schön carries in its oldest forms the meaning of bright, brilliant, and also striking, impressive.

It is uncertain whether the adjective or the noun was used first. Whenever the issue is decided, it will be done not on historical but “philosophical” grounds. Empiricists and positivists claim priority for the adjective, metaphysicians for the noun. Homer, who is often cited in the controversy, uses the adjective kalos. He applies it to men, women, garments, weapons, cattle, and dogs and seems to refer to a pleasing, sensuous characteristic; occasionally he takes kalos in the general sense of good, proper, designating a high achievement or the full realization of a potential. It is doubtful whether Homer means personified beauty when he uses the noun kallos.

To be sure, neither the etymology nor the early history of a term designating a universal idea can explain the later uses of the term, but it is not without interest for the student of the long and intricate history of beauty to see that the ambivalent use of beauty and goodness, beauty and light or radiance, goes back to the very origin of the concept, and that already in Homer's time the term was used comprehensively.” (Dictionary of the History of Ideas, 2004, pp.196-197)

Fundamental philosophical positions in the treatment of beauty assert four positions. First is the objective existence of beauty; second is the objective conception of beauty in artistic representation; third are the other instances of the objective conception of beauty; and fourth is the subjective approach to beauty (Dictionary History of Ideas, 2004). Another way of looking at the principles aims and approaches of the study of aesthetics suggests three approaches. First is the focus on “the concepts and modes of argument used in discussing beauty and an analysis of the logical and ideological questions that those aesthetic concepts and arguments imply” (Britannica, 2002). Second is the focus on the philosophical state of mind involved in aesthetic experience such as attitudes and emotions. Third is the philosophical focus on aesthetic objects (Britannica, 2002). This latter distinction between the need to address definitions of beauty, reaction to beauty, and the characteristics of beauty, resembles the issues of concern to architecture and the behavioral sciences to a large extent as will appear soon in this document.

Historically, aesthetics was primarily thought of being in the object. The decisive shift towards a subjective approach to beauty is attributed to sometime towards the end of the 17 th century early 18 th century. Inner feelings of aesthetic experience took over the qualities of aesthetics in the object. Responses such as emotions, sentiments, affections, and passions produced by the mind dominate the appreciation of beauty rather than the characteristics of the object. Beauty started to be associated with terms such as taste, reflecting subjective impressions of beauty. With the advent of the behavioral sciences involvement in aesthetics and particularly the environment behavior approach, a hypothesis was put forward that postulates aesthetics being neither in the mind nor in the environment but rather in the interaction between humans and environments; an ideological position endorsed in this document.

-

Why study aesthetics?

The study of aesthetics is important for the human well being (physiological and psychological). It is also required to understand how to resolve problems of aesthetics such as ugliness and visual clutter, so as to make places more beautiful and visually pleasing.

Perhaps the obvious reason for studying aesthetics is to understand how to deal with ugliness and visual clutter in cities. Creating a desirable mental image for cities has been a topic of many urban planners and architects (Lynch, 1960; 1981; Nasar, 1998; 1988; Porteous, 1996). Problems of aesthetics as briefly mentioned previously have to be dealt with in proper ways. The study of aesthetics assists designers to discover these ways.

Physiological and psychological benefits of aesthetics on human beings are numerous and supported by evidence from the behavioral sciences. Several studies by Roger Urlich, a behavioral scientist, have shown positive influences of viewing nature, which is one important element of aesthetics. An earlier study showed that watching a series of nature scenes can reduce the stress experienced after college exams (Urlich, 1979). In another study, Urlich (1984) found a connection between physiological well being and viewing nature. He compared hospitalized patients after surgery who watched a solid brown brick wall with others watching a small stand of trees from their hospital room. Those watching the natural view experienced fewer post-surgical complications, enjoyed faster recovery times, and required fewer painkillers. Pre-surgical tension and anxiety can be reduced upon the exposure to natural scenes (Urlich, 1986). A subsequent study by Urlich and his colleagues (1991) compared natural and urban scenes and found associations between nature scenes and both psychological and physiological benefits. The study had people watch a stressful videotape then watch a tape with natural or urban scenes. Viewers of the nature scenes such as water or park-like settings had more positive feelings, low blood pressure, slower heart rate, skin conductance and muscle tension; the latter four variables are measures of lower stress and arousal levels. Urban scenes did not show associations as clear as did the nature scenes. Moreover, scientists have argued that viewing nature scenes act as a kind of psychological vaccination or immunization which could reduce the effects of future stressors (Parsons et.al., 1998).

Aesthetic quality of spaces has been correlated with user's evaluation of these spaces. Viewers rated positively their evaluation of users in a beautiful room and negatively those in an ugly room (Maslow & Mintz, 1956 as cited in Bell, et.al, 1998). Aesthetically pleasing environments have also been found to make people feel better and feel more comfortable. A study in offices of university professors showed that students associated decorations made of plants and art objects with expectations of friendliness and welcoming of the professors using these offices (Campbell, 1979 as cited in Bell, et.al, 1998). Aesthetically pleasing spaces can create better mood that increases people's willingness to help one another (Sherrod et.al., 1977 as cited in Bell, et.al, 1998). Aesthetically pleasing spaces can assist in making people want to talk to one another (Russell & Mehrabian, 1978 as cited in Bell, et.al, 1998).

Pleasant or beautiful settings are associated with the affective quality of places and emotional reactions to environments when combined with arousal levels of environments. The classic adaptation level model of Russell and Lanius (1984) describes the affective quality of places and emotional reactions to environments by their relative position on two continua: pleasant-unpleasant and arousing-not arousing (Figure 11). This model and subsequent empirical research support the effects aesthetics can have on the emotions experienced from environments. Research also shows that creating health-promotive environments such as providing places in the city for bicycling and walking has beneficial health impacts (Frank & Engelke, 2001). In other instances, certain aesthetic elements can lead to negative or problematic effects. Decorations can be distracting (Baum & Davis, 1976 as cited in Bell, et.al, 1998).

The research evidence in favor of the positive benefits of aesthetic design on the physiological and psychological welfare of humans justifies serious inquiry into better understanding of aesthetic design principles.

Copyright © 2005, Hisham Gabr